Large trials have shown high efficacy of the combination of Tenofovir disoproxil (TDF) and Emtricitabine (FTC) used as PrEP among several risk groups. Efficacy has been shown to be highest among men who have sex with men (MSM). Both, daily and event-driven regimes showed an 86% efficacy to protect against HIV(4, 5). Efficacy among those who show good adherence is even higher and estimated around 99%(6). Although in a 2015 meta-analysis no difference in the efficacy of TDF/FTC was seen between sexes, many studies showed a reduced efficacy among cisgender women(7). For cisgender women adherence seems to be more important than among MSM, and a longer PrEP initiation time is needed to reach steady-state concentrations in the female genital tract tissue (8). New substances for the use of PrEP show promising results. Especially the long-acting injectable cabotegravir showed a better effectiveness than TDF/FTC among cisgender women but is so far not approved for prevention in Switzerland. Moreover, its high cost is an additional barrier for an off-label use. Only few data on PrEP exist for transgender men and women (9). Therefore, for both groups, the regime for cisgender women should be used. PrEP has also shown efficacy against HIV infection through needle-sharing among people who inject drugs, with a reduction of 49% in HIV incidence(10). However, for this study Tenofovir was used as a single drug and not in combination with Emtricitabine.

PrEP is recommended in Switzerland to be prescribed to persons at substantial risk of HIV since 2016(1). Since 2020, TDF/FTC has been approved by Swissmedic for the use of PrEP. As fo 1 July 2024, PrEP is covered by the compulsory health insurance as part of the SwissPrEPared program and in accordance with the FOPH reference document “Präexpositionsprophylaxe gegen HIV (HIV-PrEP)” from 31 October 2023 (40, 41). These recommendations should therefore not only assure the quality of care for people asking for PrEP, but also help to encourage physicians to offer medical supervision for people who are interested in taking PrEP.

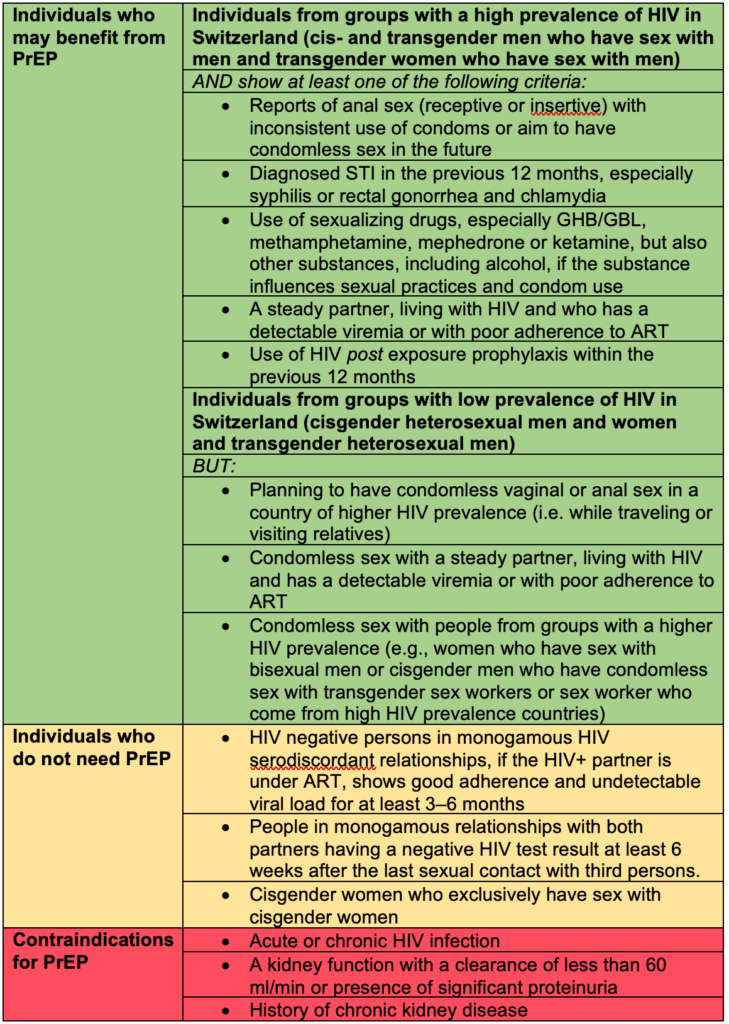

The final decision about taking PrEP is always made by the individual based on shared decision making with the prescribing physician. According to WHO, PrEP is recommended for populations whose annual HIV incidence is at least 3%(12). In Switzerland, this is mainly the case for some subgroups of MSM and transgender individuals who have sex with men(13). However, individual risk might be contextual: for instance, individuals not considered at risk in Switzerland may have a higher risk when travelling abroad; alternatively, behaviour may change over time and those not benefitting from PrEP at first may benefit later in the future. PrEP is often only needed for a certain period in life. This period can vary between a few days or years from person to person. Using PrEP as HIV prophylaxis is a personal and highly individual decision. Persons asking for PrEP are therefore in the best position to estimate their own risk. Together with health care professionals and provided information, they can establish the optimal prevention approach in a process of decision-making. Health care professionals should be capable to facilitate this decision-making process, provide easy-to-understand information, rule out contraindications for PrEP, and assess the existence of other medical conditions (such as anxiety disorders), since these could affect the decision-making process and adherence. Individuals who might benefit from PrEP, individuals who do not need PrEP and contraindications for PrEP are listed in Table 1.

Despite the importance of self-determination in the decision-making process for or against PrEP, certain persons deserve special attention as they are at a higher risk of acquiring HIV-infection and should therefore be informed and offered PrEP during medical consultations.

Individuals who benefit the most from PrEP are listed in Table 1:

Table 1: whom to recommend PrEP and contraindications for PrEP

PrEP: pre-exposure prophylaxis, GHB: gamma-Hydroxybutyric acid, GBL: gamma-Butyrolactone, STI: sexual transmitted infection, ART: antiretroviral therapy

Thanks to the good harm reduction programs, intravenous drug use is currently not a major risk for HIV in Switzerland(13). We therefore recommend maintaining these well-established and accepted harm reduction strategies and not to implement PrEP within these programs in general. PrEP may be considered in individual situations, especially for groups of people who inject drugs who so far cannot be reached with these programs, for example people who use intravenous drugs in a sexual setting or people who have not access to or fail to use sterile injecting material.

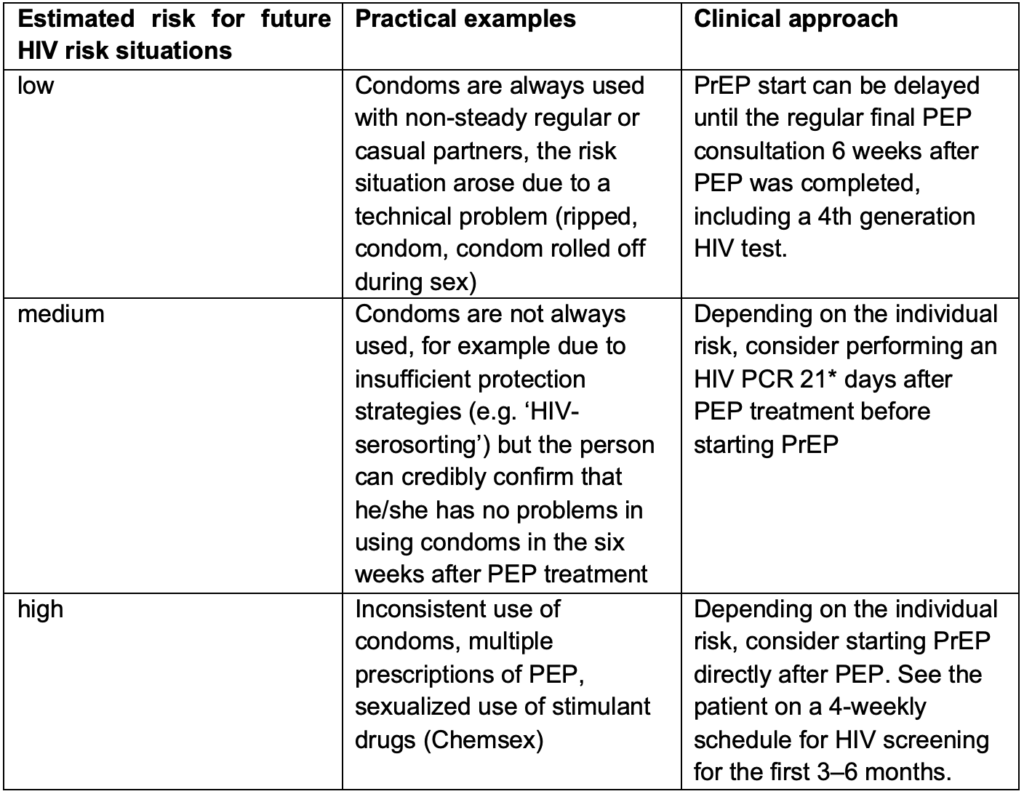

People, especially MSM, who have had an indication for PEP have been shown to have one of the highest risks for acquiring HIV(14). Information about PrEP should therefore be part of the consultations during the PEP treatment. If the person decides to start PrEP after PEP, the approach on how to start PrEP can be challenging and depends on the estimated risk for future HIV exposures. In some cases, waiting the recommended six weeks to perform a fourth generation HIV test after PEP was completed might be too long as further HIV exposure may have occurred in that time. In those cases, two practical approaches can be considered. Either an HIV PCR test can be performed before PrEP is started after a shorter window period, or PrEP can be started immediately after PEP. If PrEP is provided without a break after PEP, the point of seroconversion and therefore the time at which any HIV antibody and/or antigen test is reliable is unclear. There is not enough data to determine if PEP leads to a delay of the PCR result in case of HIV infection. Therefore, a PCR might help in the decision process but does not fully rule out HIV infection prior to PrEP initiation. In both situations – when the six weeks window period was not completed before PrEP was started – the limitations of the tests need to be discussed with the client and HIV screening tests need to be performed regularly during PrEP intake and when PrEP is discontinued. Table 2 can be used for considerations, even though each situation is individual. Consider contacting one of the SwissPrEPared physicians to discuss the case if needed.

Table 2: Considerations for future HIV risk in people who are prescribed PEP

So far, the combination of 245mg TDF and 200mg FTC is the only approved drug for PrEP in Switzerland.

Tenofovir alafenamide (TAF)

Tenofovir alafenamide 25mg (TAF) and FTC has been studied among MSM and transgender women and has shown noninferiority when used on a daily regime (15). In 2019 it was approved in the United States (US) for PrEP in MSM, but so far not in the European Union or Switzerland. This combination can be considered for off-label prescription for people with a high risk of HIV infection and a risk of developing kidney damage. However, the US approval for TAF/FTC is formally only for people with a GFR > 60mL/min (www.fda.gov). Another barrier is the high price of this product in Switzerland.

Lamivudine

WHO considers lamivudine and emtricitabine as interchangeable for HIV prevention (16). However, due to the lack of data for event-driven PrEP, we do not recommend this combination until further data is available.

Tenofovir alone

TDF alone has not been studied in MSM and is therefore not recommended for HIV prevention in Switzerland.

Cabotegravir

Eight-weekly intramuscular injections of the integrase inhibitor Cabotegravir has shown to be superior to daily TDF/FTC in preventing HIV infections among MSM and transgender women(17) as well as among cisgender women(18). However so far real life data is missing. In the US, Cabotegravir has been approved for HIV prevention in December 2021. So far, it has not been approved for PrEP in Switzerland. Off-label use is possible in theory, but due to the high costs, less of an option in Switzerland.

Studies with other drugs are ongoing and may lead to more alternative PrEP regimens in the future.

Two regimens are well-studied and showed high efficacy in large clinical trials. The daily PrEP (one pill TDF/FTC every day)(4) and PrEP on-demand (also known as event-driven PrEP), according to the IPERGAY (Intervention Préventive de l’Exposition aux Risques avec et pour les Gays) protocol(5). Both regimens differ in the lead-in/lead-out phase and the duration of the PrEP intake. In clinical practice, we often see a combination of these two regimens, adapted to the individual situations.

It is therefore crucial that the PrEP user is certain about the correct lead-in/lead-out period of the individual intake regimen. Other regimens, such as continuous PrEP for four days a week (TTSS= Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday and Sunday) refer to retrospective data only and are therefore not recommended until further evidence is made available (studies still ongoing).

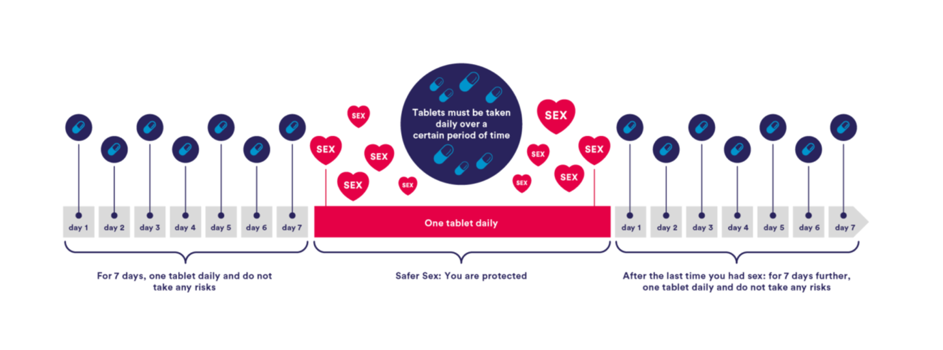

The regimen that has been best studied on multiple populations is the daily use of PrEP with a dose of 245/200mg TDF/FTC every 24 hours. This regimen has shown high efficacy among MSM, transgender women, heterosexual cisgender men and women, and intravenous drug users. (4, 19-21). A one-week lead-in time is recommended to ensure adequate drug levels in genital and rectal tissues, and is recommended to be continued for one week after the last sexual exposure. (Figure 1)

Figure 1: dosage regimen for daily PrEP with a 7-days lead in/lead out time

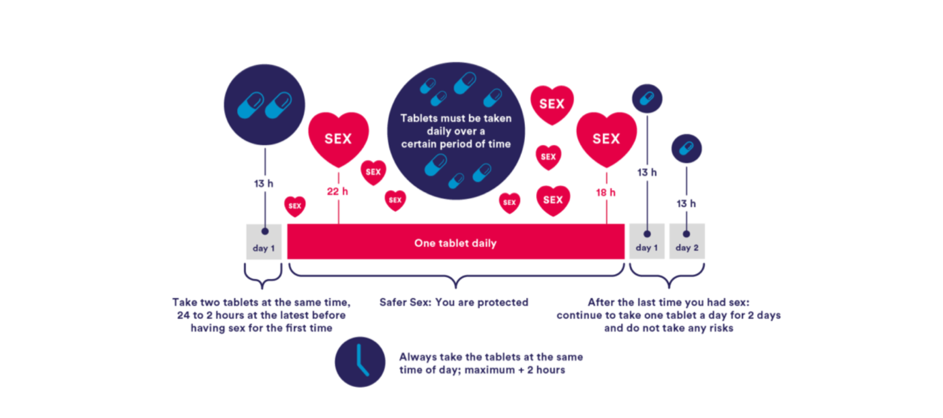

For cisgender MSM, a shorter lead-in/lead-out phase is possible, according to the results of several studies that followed the IPERGAY protocol. (Also known as ‘on-demand’, ‘event-driven’ or ‘2-1-1’ regimen)(5, 22) Although PrEP in Switzerland is officially only licensed for daily use, the ‘2-1-1’ regimen is recommended by WHO and part of many international guidelines(2, 16). (Figure 2)

The IPERGAY study assessed PrEP with TDF/FTC given as two doses 2 to 24 hours before sex, one dose 24 hours after the first (double) dose, and one dose 24 hours later (‘2-1-1’ dosing). For consecutive sexual contacts, cisgender MSM were instructed to continue with one pill per day until two days after the last sexual encounter. With every new sexual encounter, PrEP was to be initiated with a double dose, unless the last PrEP dose had occurred within 7 days, in which case only one pre-exposure dose is recommended.

In clinical practice, we often see combinations of the daily and the ‘2-1-1’ regimen. For MSM the two regimens should be no longer seen as separate options but more as complementary. As sexual activity varies over time, the best mode of HIV protection may change as well. It is therefore crucial to check regularly if the PrEP user still knows the different options of how to start and how to stop.

‘2-1-1’ is not recommended to risk groups other than cisgender MSM, especially not in women and transgender men since tenofovir levels were found 10 times lower in vaginal tissue than in rectal tissue and since clearance is faster.

No data on this regimen exists for intravenous drug users.

No data on this regimen exists for cisgender men who have sex with women (MSW). However, there is no clear rational why this regimen should not protect MSW for vaginal sex.

An intermittent dosing regimen is contraindicated for people with active HBV infection because of the risk of hepatitis flare and hepatic decompensation.

Figure 2: regimen with shorter lead in/lead out option for cisgender MSM

Some MSM might still prefer to start with a longer daily single-dose lead-in time, because they experience more side-effects with the double-dose, or they have more trust in the longer lead-in. However, in case of non-completion of the 7-days lead-in before a sexual contact, a double-dose of TDF/FTC needs to be taken at least 2h before the potential HIV exposure.

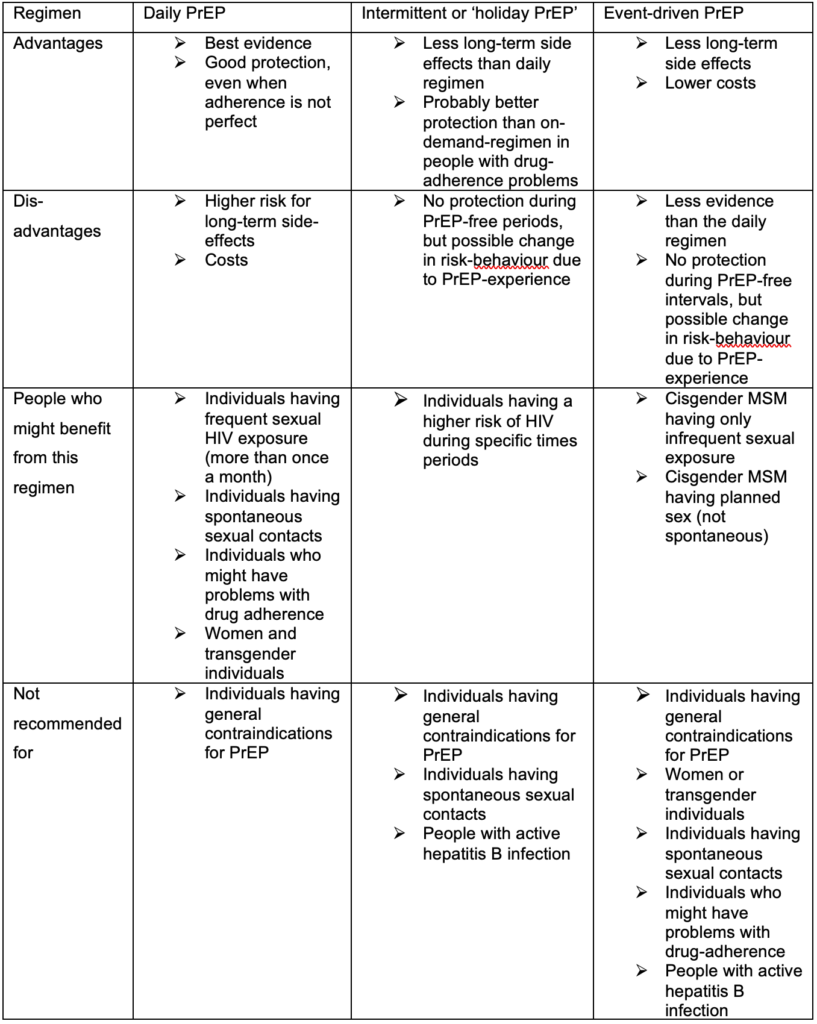

As the frequency of sexual risks for HIV varies for each individual, different regimens for the duration of PrEP are used. Besides the daily use, which is the most common regimen, some people, especially people with less sexual partners, prefer an event-driven regimen, where the PrEP is only taken before and after a sexual contact. An intermediate form is the “Intermittent PrEP” or often called “holiday PrEP” where the PrEP is taken daily, but only over a limited period and with long intervals without PrEP. The event-driven regimen makes mostly sense for people who can use the ‘2-1-1’ lead-in/lead-out. The advantages, disadvantages and target population groups are listed in Table 3.

Table 3: Advantages and disadvantages of different PrEP regimens and possible populations

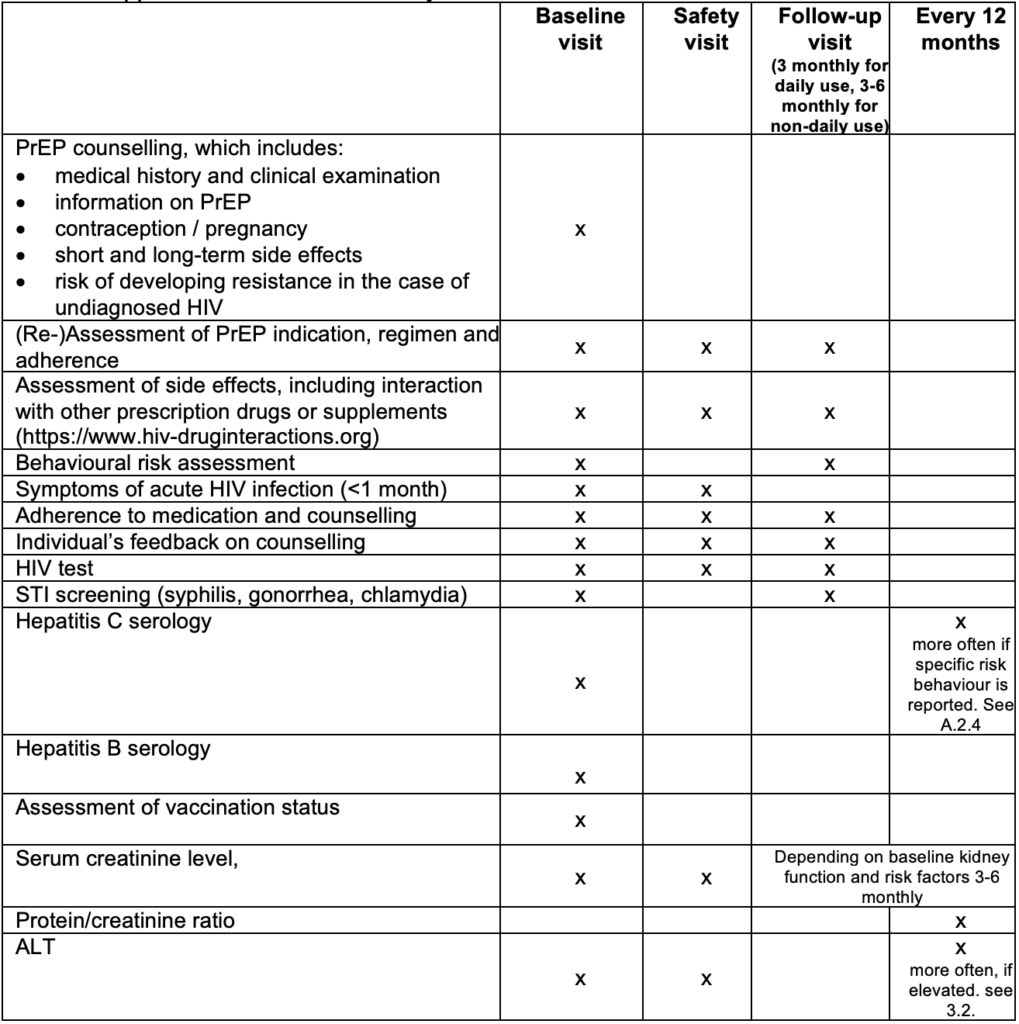

Individuals asking for PrEP will first be assessed at baseline visit (see the description below). For those deciding to start PrEP, a second visit is recommended four weeks after PrEP initiation to evaluate early side effects and to rule out acute HIV infection missed at baseline visit (HIV test window period). After the second visit, a 3-monthly plan is recommended for all individuals using daily PrEP, 3–6-monthly for individuals using on-demand PrEP, and a 6–12-monthly plan for individuals at risk of HIV who decided not to start PrEP.

Each PrEP prescription should be for 90 pills, i.e. a maximum period of 3 months for individuals using PrEP daily, or maximum period of 6 months for individuals using non-daily PrEP to ensure appropriate monitoring.

Besides the recommended laboratory tests, each visit should:

Adherence to medication is the most critical part of PrEP effectiveness. We therefore recommend evaluation of PrEP adherence at every visit and to support PrEP users who struggle with adherence. Several measures have shown to improve adherence:

The following should be addressed at the baseline visit:

In case of a contraindication for PrEP, the individual should be rescheduled within 7 days. If a person is already taking PrEP at baseline, the interventions will be adapted accordingly. If a person qualifies for PrEP but declines starting PrEP, a follow-up every 3 to 12 months is recommended to perform STI and HIV testing.

The following should be performed at a safety-visit:

The following should be performed every 12 months:

Table 4: Appointment schedule and key clinical assessments

PrEP= HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, STI= sexually transmitted infection, ALT= alanine transaminase

The PrEP start-up syndrome describes a variety of gastrointestinal and non-gastrointestinal symptoms that may occur in the first days and weeks of PrEP initiation. They are usually not associated with target organ damage, and self-limiting after a few days until a maximum 8 weeks(24).

Side effects can include nausea, flatulence, abdominal pain, dizziness, and headache. These symptoms usually occur early, but mostly disappear within the first month. They can often be managed with a symptomatic treatment like analgesia or anti-emetics, if necessary.

TDF is known to induce proximal renal tubulopathy (PRT), known as Fanconi syndrome, in some individuals (25). This is a very rare side effect where the proximal renal tubules do not absorb certain electrolytes and amino acids, resulting in a loss in the urine. Proteinuria, hypophosphatemia, hypokalemia, hypouricemia, renal acidosis and glucosuria, with normal blood glucose level, are characteristic of PRT as well as possible renal insufficiency and polyuria. In PRT, it is possible that despite the presence of proteinuria and hypophosphatemia, the creatinine clearance remains within the normal range. Most often, only some of these abnormalities are observed, and it is not certain which tests discriminate best for TDF renal toxicity.

7.2.1. Frequency of kidney function testing

After starting to take TDF for PrEP, a small but statistically significant decrease in creatinine clearance may be seen from baseline, which resolves after stopping TDF/FTC(26). There are no data for people with eGFR<60 mL/min, so continuing TDF/FTC if eGFR falls to below 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 is not advised.

Reduction in creatinine clearance while taking TDF/FTC alone is a rare side effect and many international guidelines now recommend checking the kidney function in healthy PrEP clients with no other risks for kidney failure only once or twice a year (27, 28). Although 6–12-monthly tests might be sufficient for people without risk factors, we recommend routine checking of kidney function at every visit for people considered at greater risk, for example, people with:

7.2.2. How to screen for kidney function

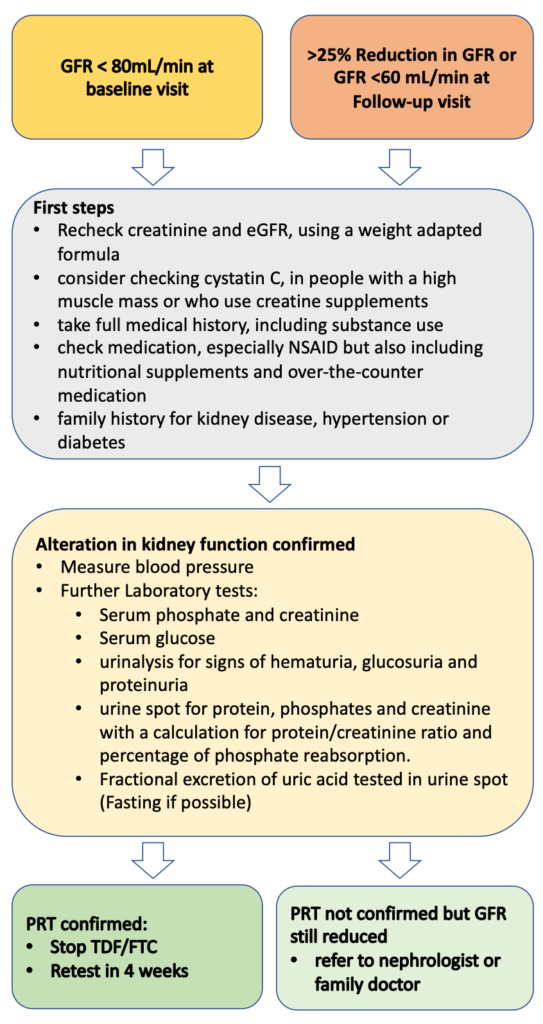

7.2.3. Stepwise approach in case of reduced GFR

In case of an alteration in kidney function, we recommend a stepwise approach (fig.3)

If a decrease in the GFR is confirmed, we recommend the following further investigations:

If laboratory tests confirm PRT, stop TDF/FTC and test kidney function again after 4 weeks. A change from a TDF to a TAF-based PrEP regimen can be considered(29). However, TAF has no label for prevention in Switzerland, and there are no generic versions available in Swiss pharmacies. Formally, the FDA label is only for people with a GFR >60 mL/min.

If lab results do not confirm PRT, still consider stopping PrEP, especially if GFR is <60 and refer the client to a kidney specialist.

Figure 3: Stepwise approach in case of alteration in kidney function

GFR= Glomerular filtration rate, NSAID= nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, PRT= proximal renal tubulopathy, TDF= Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, FTC= Emtricitabine

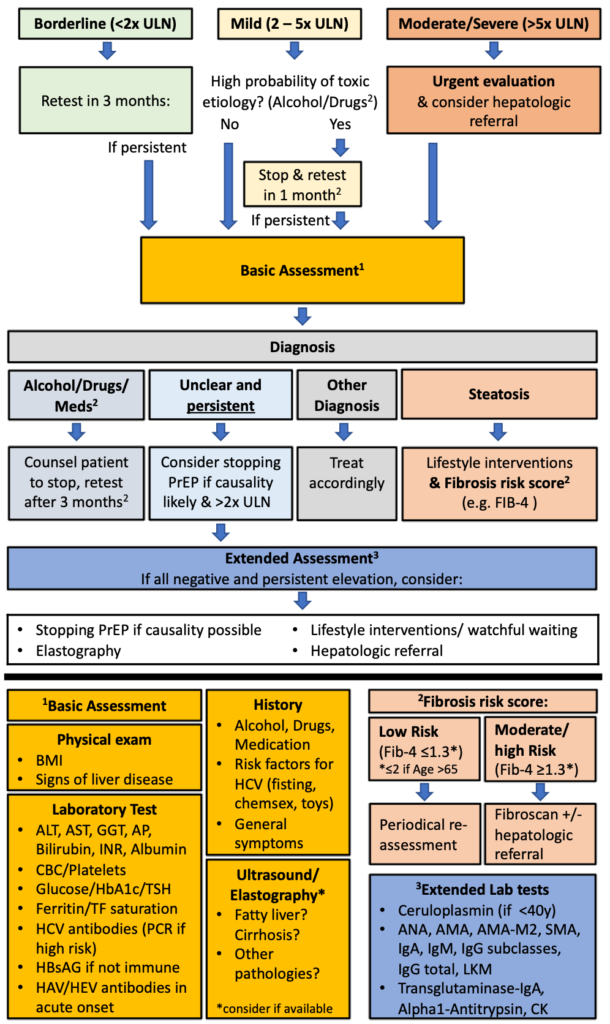

TDF can cause a mild to moderate increases in liver alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in some people living with HIV (30) and in some PrEP users (31). The clinical relevance of these findings is unclear, and most guidelines do not recommend including ALT tests in regular PrEP visits (27, 28). To our current knowledge, cases of severe PrEP induced liver injury have not been reported. As mild elevation of liver enzymes is common in the general population (prevalence estimates mostly >10%) (32), elevation of liver enzymes in PrEP clients is likely to have other origins than TDF induced liver toxicity, e.g. alcoholic liver disease (ALD), non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Liver toxicity due to recreational drug use and viral hepatitis might be more common in PrEP clients than in the general population.

The benefits (early detection of disease and potential drug toxicity) and risks (overdiagnosis, stopping PrEP unnecessarily, complications of further examinations, costs) of screening in PrEP clients are unclear, and evidence informing a recommendation is lacking. Furthermore, the upper limit of normal (ULN) for transaminases is disputed. Values in the normal range do not exclude liver diseases (33), and subsequent diagnostic evaluation of mildly elevated transaminases often do not find specific liver diseases (34). By taking into consideration that PrEP is prescribed to healthy clients as prevention, we recommend testing for ALT before starting PrEP, and every 12 months thereafter, until more data on liver toxicity is available.

If elevated liver enzymes are observed, other reasons than PrEP intake should be considered. For non-acute and asymptomatic patients, we propose a stepwise approach detailed in the algorithm below (fig.4), which we developed in adaptation to the EACS guidelines (3). When a persistent or significant ALT-elevation (>2x ULN) is observed, a basic assessment of the most common liver pathologies should be conducted. In the basic assessment, toxicity due to other medication and substances (e.g., anabolic steroids, cocaine, ecstasy), ALD, NASH, hemochromatosis, viral hepatitis and symptoms indicative of systemic diseases involving the liver should be evaluated. Individuals should be evaluated for liver steatosis with ultrasound and, if present, a fibrosis risk assessment using an established score conducted (e.g., Fib-4) (33). A low risk score allows for periodical reassessment. For moderate results preforming transient elastography and for high-risk scores, a hepatologist referral is recommended (3, 33). If available, a transient elastography might be considered in the basic evaluation, but in most guidelines, ultrasound is recommended as the primary first screening tool for NAFLD(3, 33, 35).

If no cause can be identified, and the elevation of liver enzymes persists, rare causes (autoimmune liver and metabolic liver diseases) should be evaluated. Furthermore, stopping PrEP and a hepatologist referral should be considered. For significantly elevated liver enzymes (≥ 5.0 x ULN), acute onset and/or symptomatic patients, the proposed algorithm should be used with caution and a timely, comprehensive evaluation and hepatologic referral should be evaluated. It is important to emphasize that the finding of liver steatosis might have multiple origins. If, despite lifestyle interventions, the ALT-elevation progresses or fibrosis develops, other causes should be considered.

Figure 4: Stepwise approach for elevated ALT

ULN=Upper Limit of Normal, PrEP=Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, BMI=Body-Mass-Index, ALAT=Alanin-Aminotransferase, ASAT=Aspartate-Aminotransferase, GGT=Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase AP=Alkaline Phosphatase, INR= International Normalized Ratio, CBC=Complete Blood Count, HbA1c= Glycated Hemoglobin, TSH=Thyroid Stimulating Hormone, TF=Transferrin, HCV= Hepatitis C Virus, HbsAG= Hepatitis B Antigen S HAV= Hepatitis A Virus, HEV= Hepatitis E Virus IgA Immunoglobulin A, IgM= Immunoglobulin M, IgG= Immunoglobulin G, LKM= Anti–Liver-Kidney Microsomal Antibody, CK= Creatine Kinase